I heard a voice. It broke the night. Lost in its sound was a sufferer’s story, a tale too young to swim with such frightening cadence, a tale too painful to swim at all. Oh, how did we get here? Who to blame, who to blame. Why hold a hand out if it isn’t to point a finger? Who ever to blame…

I am a 28 year old male in Ireland. Some day I will die, and the chances of me dying by suicide are higher than the chances of me dying of liver disease, leukaemia, stomach, pancreas, oesophagus, liver or colon cancer, kidney disease, lymphomas or from a serious injury or car crash. Today’s Ireland sees suicide ranked among the top ten killers in the land.

Suicide – in Ireland – is a rank epidemic that we are ultimately failing in negotiations with. We have struggled to find the vocabulary to even speak about it to one another. Perhaps we are afraid of it, and based on the figures, perhaps we ought to be too. Suicide is Ireland’s silent serial killer, a killer that trickles gently into our classrooms, softly into our children’s bedrooms, quietly into our homes and minds and often leaves little evidence of having ever visited at all. The killer punctuates our days and interrupts our nights. When we hear about suicide, we might learn it to be sudden, maybe unexpected, unneeded, unsolicited and not understood. How can we ever understand?

I am afraid of so much. In the past year, I have seen and heard things that can and will never leave me. I am not alone in this. The fixed grip of mental illness in Ireland haunts my generation on a day-to-day basis. People struggle to identify it because it is all-encompassing, and ‘mental health’ now comes with terms and conditions. For some, it might mean being unable to leave their bedroom. For others, it might mean serious anxiety issues. Others may struggle socially. Some might have down days. Some may be diagnosed with one of a host of labels; Bipolar; Borderline Personality Disorder; Social Anxiety Disorder; Depression.

Terms and conditions apply to all aspects of mental health in fact, not only the labels of illnesses, but also within the vocabulary of various campaigns, individuals and organisations’ work. We see ambiguity in our understanding of ‘mental health’ within the nebulous phenomenon of awareness campaigns, of which we are seeing more and more of. The discourse of ‘awareness’ is defined and measured differently in each campaign, therefore the expectancy of outcomes from each campaign shifts accordingly.

It seems that because of this, we have created a buzz of confusion surrounding mental health. Within the confusion, we are fretting over the right etiquette with which to use when even speaking about mental health. The worry here is that this confusion will lead to some thinking of ‘mental health’ as dirty words.

We often even think of ‘mental health’ as connoting something ‘bad’ or ‘ill’. When we hear ‘mental health’, we think of all the types of illnesses someone may have under that umbrella. That type of thinking would never happen when one simply thinks of the connotations of the word ‘health’ alone; all of the conceivable illnesses or ailments simply would not spring to mind when thinking simply of ‘health’.

This sense of confusion surrounding mental health is ostensibly a result of the need in Ireland for sufferers voices to be heard, and that is something we must focus on when moving forward in our discussions of mental health. We must not lose one another within the confusion. Cohesion simply has to be key.

This confusion has led to the inevitable cracks beginning to slowly show. If we are to progress in the discussion on mental health, we must do it together in a meaningful, tolerant and responsible manner. History shows that successful lobbying – be it with regard to fracking, smoking bans, public sector reform or otherwise – has happened when the lobbyists own the terms of the debate. That is who we can be. This is what we can do. Mental health illnesses and individual stories make up the fabric of one cohesive movement; one people; one voice; one movement; one fight. The subject of mental health reform is in its relative infancy, and we must support those with the ability to instigate tangible change to move the conversation to the next stage.

The media also has a serious role to play in the movement for mental health reform. The media has a sociocultural and moral responsibility in choosing how to portray mental health events and campaigns, or whether to portray them at all. If the media are poorly selective in their choosing and framework of reporting, then disputation between us – one another – is sure to strive. Instead, this cohesion must be embraced and championed by both mental health campaigns and media alike. One people; one voice; one movement; one fight.

These seem to me fundamental needs for many sufferers of ill mental health, and the discussion for the implementation of these things must be activated for us to begin to see tangible results within the confusion and mess of the mental health system.

We must not lose sight of one another amid confusion. This must be cohesive – one people; one voice; one movement; one fight.

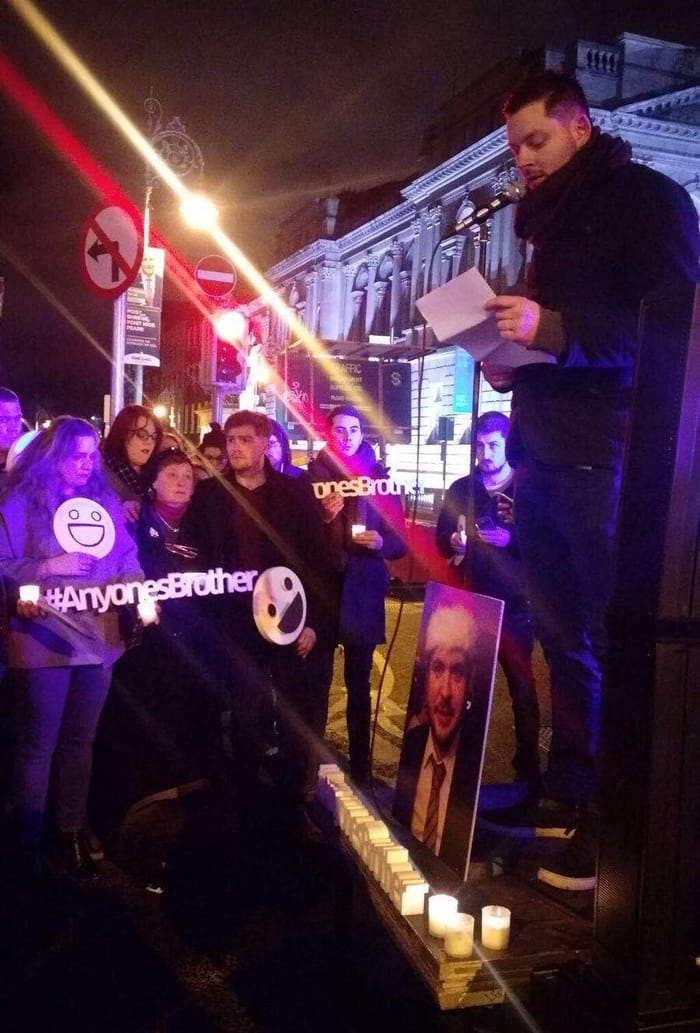

We lost sight of hope for Caoilte amid systematic injustices, confusion and wrongdoings within a seriously flawed system. That cannot happen anymore.

Let us be the voice. Let us break the night.

If you are someone you know has been affected by suicide get the help you deserve – Some useful information via yourmentalhealth.ie